Don’t Make Drama Films

If you’re an indie filmmaker trying to sell a movie, here’s a hot tip from the trenches: don’t make a drama …

Not unless you’ve got a celebrity on call, a slot in Cannes already confirmed, or a high tolerance for being ignored in your inbox for months at a time.

This is the reality of micro-budget drama movies and it hurts. It hurts because I love dramas. I love watching them and I enjoy making them. I love characters sitting around a table saying things they don’t mean, and meaning things they don’t say. I love quiet shots that last a little too long. I love the complexity of human relationships and the slow burn of emotional truth.

But the market? The market is begging you to make anything else.

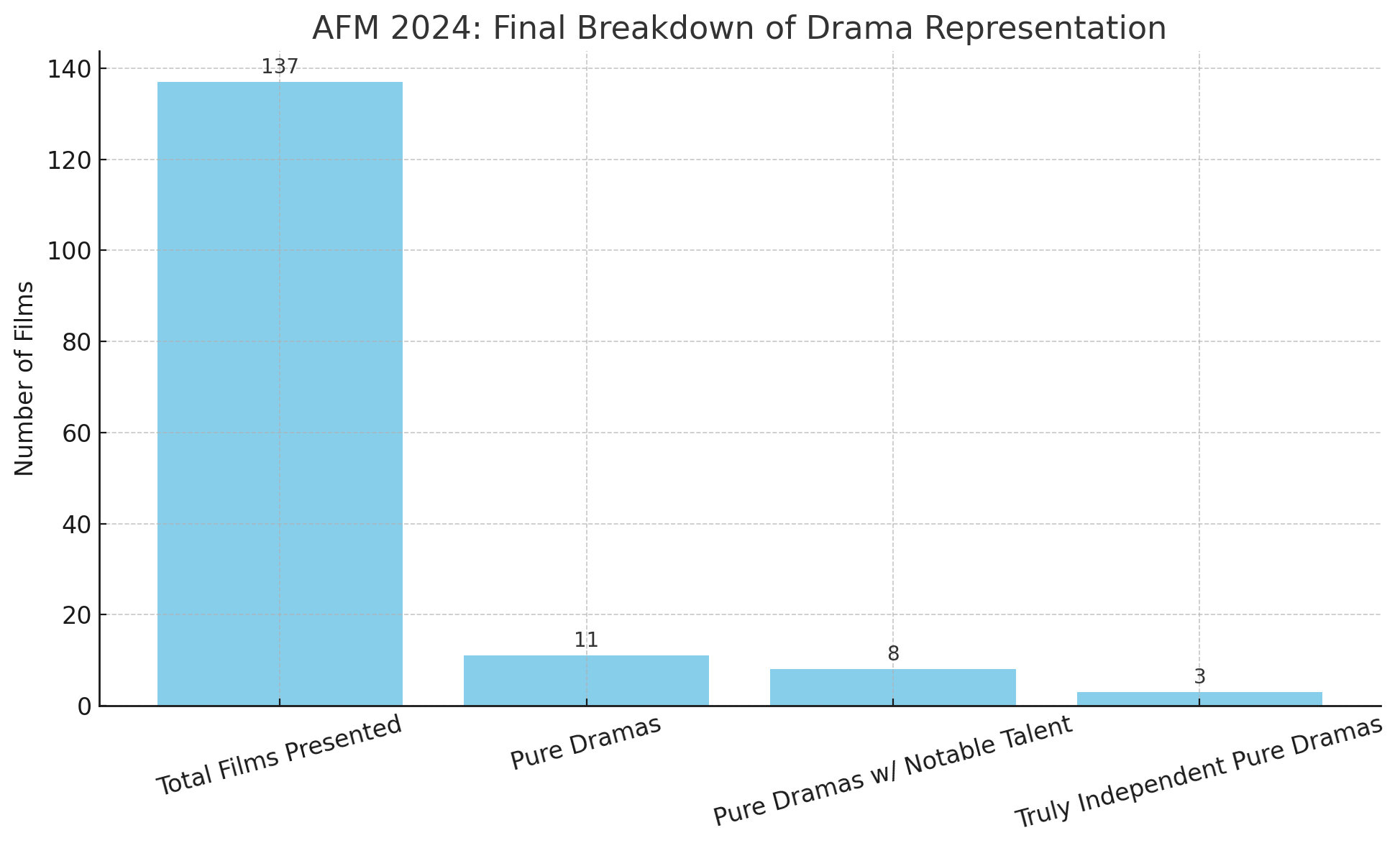

Look at the most recent American Film Market (AFM). Out of 137 films presented by international sales agents, only 11 were pure dramas, meaning films that are character-driven, grounded in reality, and not propped up by genre elements like horror, thriller, or romance, etc.

And then when you take out the films with stars or prestige directors, you’re left with only three. Three pure dramas – no celebrities, no high-concept loglines, no laurels to prop them up. One of them, Between Borders, follows an Armenian family fleeing during the Soviet collapse. The Snare is a coming-of-age story about a high school student pressured to become an informant. And Death of a Comedian centers on a fading TV actor confronting his mortality. Three films trying to stand on story alone. 3 out of 137 films. 2.2% of the entire AFM slate.

Meanwhile, the dramas that get attention are the ones with star power or festival laurels baked in. Father, Mother, Sister, Brother, directed by Jim Jarmusch, features Cate Blanchett and Adam Driver. The Great Lillian Hall stars Jessica Lange, Kathy Bates, and Pierce Brosnan. And then there’s Pieces of a Foreign Life, riding its Cannes buzz on the back of Holy Spider star Zar Amir Ebrahimi. These films aren’t just dramas – they’re packaged. It’s not the genre that sells. It’s the names and the festival pedigree.

And the rest of the AFM films? It’s a genre buffet, of course. Thrillers, horror, rom-coms, sci-fi, action, true crime. Even a hippo survival movie called Hungry about a group of tourists stalked by a hippo in the wilderness. Okay, I admit that one sounds pretty cool. But the point is almost every single film is pitched with a hook that promises speed, spectacle, or something just absurd enough to catch the eye.

Drama, on the other hand, isn’t selling unless it comes with a safety net like Cate Blanchett. Subtle human stories without prestige? They’re not just a hard sell, they’re almost invisible.

And that’s the hard truth. Which is too bad for us, because subtle human stories are exactly the kinds of films we like making. And with our micro-budget approach, we’re rarely in a position to chase prestige or generate buzz before the film even exists.

We’re living this right now with our latest feature, After the Act. It’s a beautifully crafted arthouse drama. It is one of the best looking films we’ve made. It has heart, it has soul, if you’ll indulge a little pride. It’s everything we set out to make. But when it comes to finding a distributor or sales agent, the feedback is always the same:

“Love the story and the performances are compelling, but you’ll need a major festival selection to generate interest.”

This isn’t new. Back in 2018 we released Friends, Foes & Fireworks, an improvised New Year’s Eve drama. It’s raw, intimate, and still one of our favourite experiences on set. But it never turned a profit. It’s been out for seven years and remains in the red.

Compare that to our more niche, genre-adjacent projects – In Corpore (an erotic drama) and Cats of Malta (a documentary) – and the numbers tell a different story. Those films found their audiences. They had built-in markets and elements that made them easier to sell. Not necessarily better films, but easier sells.

It’ll be interesting to see how After the Act compares once our other 2025 drama, ForeFans, hits the market. This one’s an erotic drama set in the world of camgirls. And honestly, I suspect we’ll have an easier time generating buyer interest in ForeFans.

I see this echoed across indie filmmaking groups online. A filmmaker, Jason Park, recently shared that his drama, which he insists is the best thing he’s made, is slow to get picked up by any streamers. But his rom-coms and thrillers? Snatched up immediately.

Another filmmaker, Joel Hills, replied:

“Generally speaking, people don’t want to watch a group of unknown actors delivering amateur drama performances on a zero-budget film set.”

Harsh, but all evidence points to it being the reality. It’s demoralizing, isn’t it? Especially when what you want to make isn’t flashy or trending. When all the advice is telling you to pivot to horror or action or influencers playing heightened versions of themselves.

So, where does that leave us?

I don’t have a clean answer. I’m still figuring it out myself. There’s a gap between the kind of films I love making and the kind that buyers want to buy. But I keep coming back to this: I’m an artist first.

I didn’t get into filmmaking to become a content factory. I got into it because I believe in the power of human stories – slow, complex, and sometimes commercially inconvenient. I still want to tell those stories, even if the road is longer. Even if it’s harder to sell.

But that doesn’t mean I’m blind to reality. I’ll keep learning, and experimenting, and maybe I’ll add some more market pleasing elements in my next film, because at the end of the day to keep making films, I need to actually turn a profit. That’s the push and pull: the business side knocking up against the art, again.

So yeah, don’t make drama … unless, like me, you can’t help yourself.

Written by Ivan Malekin

References

List of AFM 2024 Sales Agencies and the Films they are Representing